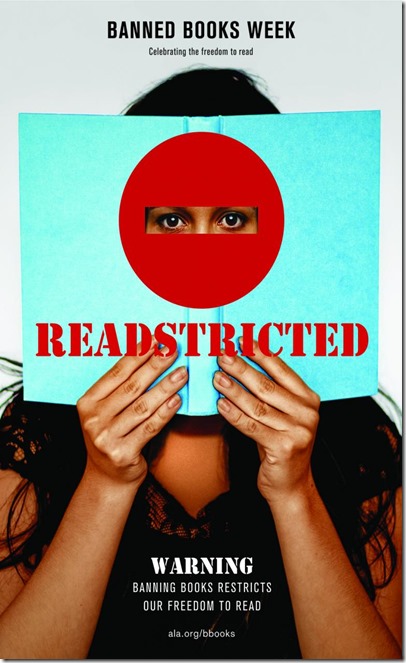

While I’ve effectively stopped blogging as of late (except for a couple of items over at INALJ), I did feel strongly enough to revisit something I’ve written about just about every year since I started this blog. Once again, Banned Books Week is upon the library world. It is the time of year to break out the CAUTION tape, line up the usual suspects on a book display, and remind the public that history is littered with people being jerks over stuff they don’t like. The “here for now, gone next week” brevity of this event just shows how important the topic in libraryland. (I digress before my blood pressure shoots up high enough to smother an oil well fire.)

With each year, some of the same tropes get trotted out for their annual airing. Some of these originate from those who hate freedom who find folly in Banned Books Week while others originate from the lies we tell ourselves. These are tropes that need to die or at least be wounded to the point where they should slink back to their cave and swear off the world of humankind. As much as I am loathe to make a listicle blog post on the one occasion that I feel like writing here, it is best served that way.

So, without further ado:

A Ban Isn’t a Ban if it is Available Elsewhere

This is the best kind of correct: technically correct. Just because the local public or school library removes a book from the collection doesn’t mean it’s a ban because you can get it from a bookstore, Amazon, and any number of other retail outlets. It’s the same logic that (when tortured) would support the notion that Cuban cigars are not truly banned in the United States because you can drive to Canada to get them. Or that you can still permitted to get married in Rowan County, Kentucky since you can drive to another clerk’s office to get the license. This trope is offered like a riposte to the Banned Book Week sentiment as if it were a damning overlooked detail.

The trouble is that it is a superficial sentiment that largely misses the point about infringements on individual freedoms of expression (including choice of reading materials) while ignoring economic inequity and the digital divide. A book removal is an affront not simply to the individual but to the overall community. It is an limitation of expression not in some faraway or abstract place, but within the boundaries of the community. It’s the application of personal values on a community good that I find so loathsome and tiresome. I think of the quote attributed to Aristotle: “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it”. Such is the essence of a library: a place for entertaining such ideas for examination.

The “you can buy it elsewhere” notion fizzles under scrutiny because of its underlying requirements: finances to purchase the title or work in question and/or information access (formerly analog but now mostly digital). With the former, the onus is placed on the individual to spend money to purchase material that was already judged to be worthy of inclusion in a library, be it public, school, or academic. It creates a financial burden that flies in the spirit of the words etches across the façade of the Boston Public Library, “Free to All”. There is no asterisk at the end of that motto denoting terms and conditions that apply to certain disliked materials.

In looking towards the latter, information access is a key librarian principle. While it is better known in some ways as the digital divide, the removal of material due to subjective personal values is a barrier for others. This is one of the core objections to filtering software on computers; not simply that it doesn’t work well (they really don’t), but that it usurps the end user’s judgment about which sites are (for lack of a better phrase) “good or bad” for them. The library is there to facilitate information access, not limit it in the old gatekeeper style that we have surely moved away from (right, guys?).

“It’s available elsewhere” is a perfectly valid response… so long as you’re not the one that has to travel to get it. If you’re are the other end of that equation, you will probably much different about it.

Arguing over the word “censorship”

It’s eternal and pedantic like much of librarianship, but inevitably someone brings up the dictionary definition of “censorship” within the context of Banned Books Week.

“Actually, ‘censorship’ can only be done by government…” emanates from their smug mouths as if access to Wikipedia was like vacationing in the Hamptons of the Internet. It’s an English lesson wrapped up in the history of public morality being controlled by royalty, government, or religious forces. And while I am a fan of history, it ultimately misses an intrinsic point: things change.

This most appropriately includes the meanings and usage of words. It’s how the word “literally” has been morphed to mean “figuratively” in certain contexts. It’s how “gay” turned from the happy emotion to denoting homosexuality. Language evolves and that it is no less what happened with the word censorship.

Just accept that censorship has evolved in its definition to include non-governmental and personal applications of one person suppressing another. Then move on to the bigger and more important arguments that need to happen rather than get bogged down on one point.

You know what they mean when they use the word. Don’t be that person.

The name itself: Banned Books Week

Like censorship, what it means to be “banned” has changed over time. In the past, it was a blanket prohibition to booksellers or having it removed from library shelves or a combination of both. Now, it is more about the local level when it happens at the public or school library; it is a ban that affects a generally smaller community than in years past. Without rehashing the “available elsewhere” point (too much) or the changing definition of the word “censorship” (too much), what it means to be “banned” has taken on new meanings.

“Banned” is no longer a status bestowed by the government, but by individuals or groups looking to remove library material that they find repugnant. It has shifted from a national or state or even city-wide determination to the local and personal level. It’s not the Mayor or other local elected official condemning a book (unless you live in Venice), but other citizens within the town enforcing their mores on others. Banned is not the government saying “you can’t have that”; it’s your seemingly friendly neighbor, the counter person at the deli, the dog walker at the local park who is telling you that this book or movie is so bad that it cannot dwell on the shelves of the library. The concept of “banned” is now so very personal for its level of disruption strikes at the individual within the community.

Personally, I like the name ‘Banned Books Week’ because I do love alliteration. The whole thing just rolls off the tongue with the right amount of consonants and vowels in succinct syllables. Professionally, it conveys an overt meaning very well to the library world as well as the general public. Banned books! Not challenged books or pornographic books or Satanic books, but banned books. The word “banned” itself grabs you with thoughts of illegal, immoral, or other unsavory characteristics that have been attributed to some of the works that get mentioned on the ALA’s Most Challenged list.

If someone can come up with a better name that doesn’t sound like a mouthful of librarian jargon, I’m listening. I’m not even going to bother with the “it’s tradition” point because I’m ok with making new ones in this case. But it better be fun to say if you want my vote.

All Challenges are the Same

I’m certainly not the first person to say it, but the open secret in libraryland is that not all challenges are the same. And yet they get lumped into one giant statistical pile in which the most minor (“I think this book should be for 5th graders, not 3rd graders”) is comingled with the most outrageous (“Harry Potter is Satanic and needs to be destroyed” and its hyperventilating ilk). For a profession that values accuracy, that’s an infuriating oversight.

I understand that collecting challenge information is not the easiest. From my own passing research into the area, the profession is disappointingly remiss at reporting, responding, or even actually following procedures for material challenges. The professional ideal is cast aside in the face of naked pragmatism whose purpose is to avoid any “drama” at any cost. Thus, it leaves a rather apparent incomplete picture that makes it harder for Office of Intellectual Freedom staffer and state association Intellectual Freedom committee members (like myself in NJLA) to form a strategy, offer education and/or support, or even know what the hell is really going on at times. Better reporting and reporting practices need to be instilled values not simply at the job, but in the MLS/MLIS graduate programs that educate the next generation of librarians.

A lack of subclassification for materials challenges between “move it to another age group” versus the “get it out of here” crowd really needs to be addressed. One size does not fit all when it comes to recording challenges.

We are smarter and better than that.

Banned Books Week Doesn’t Matter

Just as I was starting to write this blog post, an article from Slate saying exactly that crossed my social media feeds. No one bans books anymore so we can all go home now is my ungenerous summary of that article because a simple eyeroll of contempt simply won’t suffice. Some of the points of the articles have been addressed a thousand words ago, so let me get at the heart of the matter.

Intellectual freedom requires constant vigilance against encroaching forces. It’s not a hobby, a part time job, or a thing you do while you are waiting for the bus, but it is a principle that requires a steady commitment across a vast network of individuals. It’s the big things like the wholesale scooping of metadata by the government and the little things like the grandmother whose thinks a ten year old LGBT anthology is “child pornography”. It’s a value that is important not simply to librarian profession, but what it is to be free thinking person of the world (and, personally, a citizen of the United States). This is the border over which I stand watch not simply for me but for all those who will be able to pick up a book or movie or music or load a website and not give a second thought as to whether it is acceptable by the greater society. That is why intellectual freedom is important and why it demands such care.

If you still think that Banned Books Week is a celebration of not having stuff be banned, then let us have that victory lap. It’s another trip around the Sun where we can say that we did our duty. It’s a yearly reminder of how far we have come as a society and how much further we still need to go.

Banned Books Week matters because what it represents within history, society, and culture matters: the thoughts, ideas, and dreams that make us human beings.

Previous years:

Banned Books Beast 2014

Banned Books Bollocks 2013

Banned Books Bullshit (2012)

Banned Books Bullshit, Revisited (2011)

Banned Books Week 2010

Banned Book Bullshit (2009)